The Drongo, Interview #2: Chris Stasse

by Maxwell Joslyn. (updated

From Drong Beach, California comes another interview with The Drongo.

Subscribers are up 20% since the first issue! Thank you all for such positive feedback. If you're not signed up, subscribe to The Drongo (it's free!), and you'll get these interviews by email twice a month.

The Drongo: Chris Stasse and I have been friends since we met as college sophomores taking Second Year Chinese. Today's interview guest is a supreme shenaniganeer, one who acts with vigor and learns with rigor.

Chris Stasse: Hey all, I'm Chris. I like poetry. Also, I like dance, many sports, tea, cooking, movies, Han Yu, and Emerson. I have an obsessive interest in Chinese which will likely be my downfall, even as I savor the archaic and in many ways hopelessly poetic qualities of its modern and ancient legacy. It seems my personal values are also archaic and hopelessly poetic, which is probably the best reason I can give for why I study Chinese.

Maybe I will open a soup restaurant in China someday. "Super Soup Yum 苏坡苏坡香": a delicious harbor for all world-weary drongos!

The Drongo: Having heard Chris's menu proposal, I'll be at Super Soup Yum on opening day.

Chris, you've immersed yourself in Chinese language and culture for nearly a decade, including three years spent living in southern China. What led you to start learning Mandarin, and how have your motivations changed over time? What is the most meaningful element of your current studies?

Chris Stasse: I guess in the beginning, learning Mandarin was a result of traveling in China after high school on a "gap year," and wanting to communicate in a more effective way with people I met there. It was really a practical tool. As a freshman at Reed, I decided it couldn't be a bad idea to learn more about the language, and I needed the language credit, anyway. That's more or less what started it.

From 2012 to 2016, different things pushed me from a relatively casual relationship with Chinese to it being the center of my studies. I was good at it. I made enough improvement with regular studies to have a sense of accomplishment. I had good teachers. On a social level, different relationships at school became more and more connected with Chinese: I befriended other students studying it, and also dated a Chinese woman.

Some time in late sophomore or early junior year, Chinese had become not just a fun thing I was doing at school, but also the answer to something I wanted badly: to leave Reed for a while. There was an option to study abroad in Fuzhou, China for very little cost. I left in spring of 2015.

In Fuzhou, Chinese was no longer a side-show. It was the center of my studies, and the necessary medium for the expression of my personality and interests. I was reading, talking, writing and listening a lot, every day. About a year into the program, I realized that Chinese was not just an excuse to be in China, was not just a tool for interacting with different people, was not just an interesting school subject. It was a fundamentally different way to express myself compared to English. I could say things I couldn't say in my mother tongue.

It wasn't "bigger" than English, but it was older, prettier, and definitely wiser. I remember asking myself, "What would you do if you could do anything in your life, no matter how crazy?"

At the time the answer seemed ridiculous, but it went to my core:

"I would write poetry in Chinese."

Currently, I am learning Classical Chinese. I remember Hyong Rhew [Professor and Chair of Chinese Literature, Reed College] once warned me that if you don't study Classical, your Modern Chinese won't go anywhere. He was right: if you want to be really good, you can't ignore Classical. Anything beyond a conversational felicity requires some grounding in it.

The Drongo: Traditional Chinese cultural practices range from tai chi to papercutting to poetry to opera. You have chosen to concentrate on calligraphy. Can you put into words the experience of studying calligraphy, and the feeling of actually performing it?

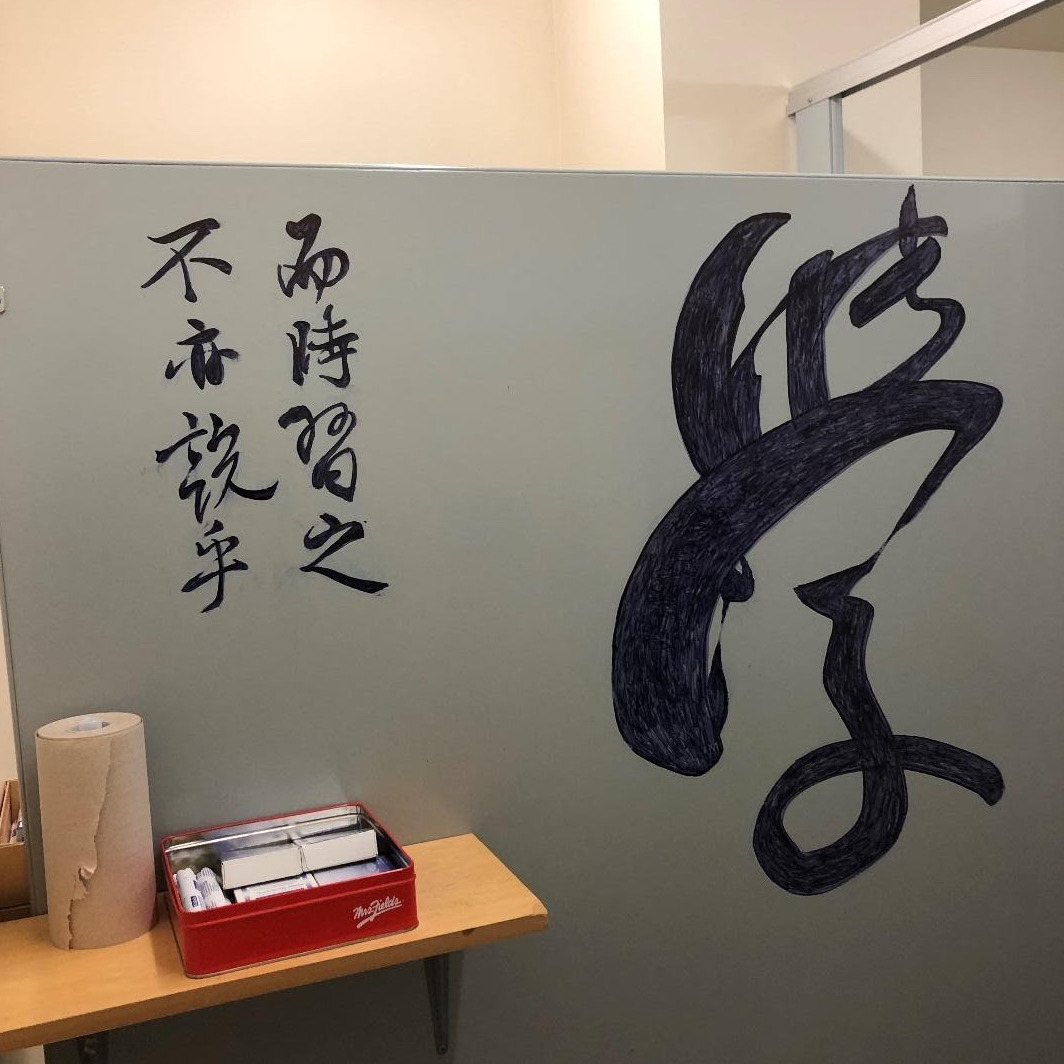

Chris Stasse: As this is a website dedicated to drongos, I have decided to share a drong-venture calligraphy project: graffitiing the Reed College Chinese department's bathroom stalls. The phrase is the first sentence from The Analects: 學而時習之不亦説乎. ["Is it not pleasurable to learn, and to persevere in practicing?"]

The Drongo: That's a spectacular piece of work. You're a drongo extraordinaire.

Chris Stasse: Just as with Chinese itself, I did not think much of calligraphy when I first started learning it. The decision to try it was basically whimsical. I had never really studied a visual art before, and I needed to take an elective in the Fuzhou program.

However, again as with Chinese, I found that I enjoyed calligraphy more than expected, and that enjoyment was visceral, not intellectual. I've thought about how, in grade school, I was really attracted to the idea of learning cursive. I seemed to be in the minority among my classmates for taking cursive practice seriously, and eventually making it my default handwriting. After high school, I started journaling a lot. Part of the journaling habit was not just reflecting on recent thoughts or interesting quotations, but actually immersing myself in the physical act of writing.

To make the writing itself beautiful seemed to be an exercise in piety to the ideas I was transcribing. I think that is the same set of motivations I ultimately took to calligraphy. I am inspired by ideas I encounter, or about which I am writing, and I want to express them in a way that is personal and has the potential to be artistically evocative.

Because of the nature of Chinese characters vs. the Roman alphabet, as well as the nature of the brush vs. the pen, what you can convey with Chinese calligraphy is much more expansive than what you can convey with English calligraphy. Artistic urges I have had since grade school have found a much wider and deeper outlet in Chinese. There is a visceral, cathartic, almost primal enjoyment I get from writing calligraphy -- and then the things I write get to be nice-looking. In some ways, I think I have a "purer" relationship with calligraphy than with Chinese, in the sense that it is really just a hobby I do for fun. There is a lot of work with Chinese to get the expressive and comprehensive skills, but the "work" in calligraphy actually makes me feel relaxed.

The Drongo: Now that we've seen Chinese at its most visually expressive, why don't you share one or two Chinese quotations or phrases which exemplify what makes you find the language so fascinating? Anything goes.

Chris Stasse: I mentioned earlier that I found Chinese "older, prettier, and wiser than English." Let me give some examples.

Chinese has endless idioms, which are most often four-character phrases.

Older

不日不月

bú rì bú yuè

This example literally means "no sun no moon" or "no day no month." What could that mean? The phrase comes from the Classic of Odes, one of the world's oldest collections of poetry, which dates back to roughly 1000 BC. The actual meaning is something like "unable to use days or months to record," or simply "an unimaginably long time."

The phrase is extremely old (and reads as being very archaic now), but the characters that compose it are very simple. This is a major difference between the ancientness of Chinese and the ancientness of Romance languages: whereas one would have to study Greek or Latin to know the ancient roots of many English words, many Chinese characters have not changed in thousands of years, and appear in phrases as old as China's earliest dynasties.

Prettier

離緒縈懷

lí xù yíng huái

This phrase almost sounds like a four-character idiom, but is not. Literally, it means: "departure feelings entwine bosom." I would pick out at least three reasons this phrase is more aesthetically pleasing in the original than in its translated counterpart.

First of all, English sounds weird if you eliminate articles like "the." Compare "entwine bosom" with "entwine the bosom" (or "my bosom," etc.). In Chinese, and especially in Chinese poetry, "content words" can be arranged to create meaning themselves, without adding many "function words" for structure. This often reduces clarity, but creates more potential for "uncluttered" aesthetic expression.

Second, this phrase contains the character "緒 xù," which I have translated using the very weak English "feelings," but which originally means "the ends of threads." In its practical usage, this character is often used to talk about subtle thoughts or emotions lingering in the mind. The choice of "緒 xù" works perfectly with the next character "縈 yíng," "to entwine." Put together, the phrase conveys sorrowful "strands" of emotion wrapping around one's bosom. It would be difficult to achieve the metaphorical resonance and brevity of the original in an English translation.

The third and final reason this phrase stands out is not for its meaning, but its visual complexity. These four characters are noticeably denser than the previous four characters. They are complicated, requiring many more brush strokes to write, but are still relatively well-balanced. This is the sort of phrase I would enjoy transcribing into calligraphy.

As a disclaimer, it is obviously true that there are many examples of English poetry which would translate clumsily into Chinese. I bring up this phrase only to demonstrate how certain features of Chinese -- the visual identity of characters, the lack of dependence on function particles -- give it unique aesthetic potential.

Wiser

發了橫財不散財,必有災禍天上來

Fā le héngcái bù sàncái, bì yŏu zāihuò tiān shàng lái

The above aphorism means something like, "To accumulate and not disperse will result in heaven's curse." (I tried to retain the rhyming feature of the original.)

There are endless idioms in Chinese; there are also endless aphorisms and proverbs. I have often wondered what it must be like to be Chinese and inherit this kind of over-rich linguistic tradition. It must be a curious weight to bear: both a source of pride, and a daunting shadow to live under.

More than any other culture I can think of, China tends to monumentalize the language of its ancestors. To Chinese people, Chinese is not just a language, but a heroic cultural achievement. The ways in which Chinese characters were invented and recorded have been carefully mythologized and integrated into China's self-perceived identity. Chinese has been the vehicle for this civilization's sense of uninterrupted cultural transmission for millennia, and along the way it has accumulated a dizzying mass of useful sayings. This is a language that is wiser than any one of its users.

The Drongo: Keep expressing yourself with phrases like "wiser than any of its users," and I'll be your friend for life.

Our last question is simple, but it needs a bit of background. At 19, with no Chinese ability to speak of, you traveled from Beijing to Tianjin, and it took you a week because you walked. Later that year, you squatted for weeks on an abandoned helipad in the forest. Now, at 26, you live in a Dodge minivan which you and your dad converted into a mobile scholar's hut.

What is it that compels you to be such a drongo?

Chris Stasse: I think doing this stuff comes from an intuition that I am most likely to learn something when I am outside what I am familiar with. I need to remove the things I normally take for granted to see what is essential.

If I want to learn, I can't just go do it; I need to actually make myself vulnerable to learning. That is the purpose of an adventure: to put down the accumulated props of my life and allow myself to react to completely new situations. There is value to being at my wit's end.

The Drongo: Why, you've articulated the whole drongo ethos in one pithy phrase!

Chris Stasse: Before we conclude, I have one more thing to share: a freestyle dance video.

The Drongo: My god, look at those moves. If you keep recording dances, I'll keep watching. How about doing one set to Daft Punk called "Harder, Better, Faster, Dronger?"

ⵘ ⵗ ⵘ ⵗ ⵘ

Thank you very much, Chris, for sharing your thoughts with The Drongo. May you embark on a million adventures. Readers can contact Chris at evanstasse@gmail.com, or read his irregular 2011-2017 travel blog at https://mytb.org/evanstasse.

If you enjoyed this interview, share it with your friends, followers, and family. Show them Chris's champion calligraphy! Here's the web URL:

https://www.maxwelljoslyn.com/thedrongo/interviews/chris-stasse

Or share on social media:

Interview #3, with Carla Paloma, comes out at the end of January. We'll see her gorgeous pottery, and talk about running an artist residency located in a historic and unusual location! Don't delay: subscribe now to get Carla's story right in your inbox.